Birds possess a remarkable array of features that set them apart from other living animals, yet their ancient ancestors would have appeared strikingly different to the feathered creatures we recognise today.

++ Israeli airstrikes target iranian military and nuclear leadership in unprecedented operation

The origin of birds dates back to the age of dinosaurs, when they began evolving within a subgroup of these prehistoric reptiles. While palaeontologists have uncovered several transitional fossils of bird-like species, identifying the very first bird remains a complex challenge. The distinction between birds and non-avian dinosaurs is, in truth, a human construct, with no definitive dividing line in nature.

Over millions of years, birds gradually developed key traits that distinguish them from all other animal groups alive today. These include visible features such as feathers and wings – the latter shared only with bats among living vertebrates capable of powered flight – as well as less obvious ones like hollow bones, relatively large brains, and warm-bloodedness. Modern birds also lack teeth, although certain species, particularly aquatic ones, sport ridged beaks that function similarly by helping them grasp slippery prey.

However, these hallmark features did not all appear at once. For example, the toothless beak seems to have evolved around 120 million years ago – quite late in avian evolutionary history – while hollow bones may have developed 100 million years earlier. According to Professor Daniel Field, a palaeontologist specialising in avian evolution, it is the combination of such features that allows birds to be identified as a distinct group among living creatures.

Among the most recognisable traits of birds, feathers are now believed to have evolved in non-avian dinosaurs well before the first true birds appeared. The earliest bird-like animals were in fact feathered dinosaurs, emerging around 165 to 150 million years ago from a group known as theropods. These bipedal dinosaurs, defined by three forward-facing toes, include not only the ancestors of birds but also iconic predators like Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor.

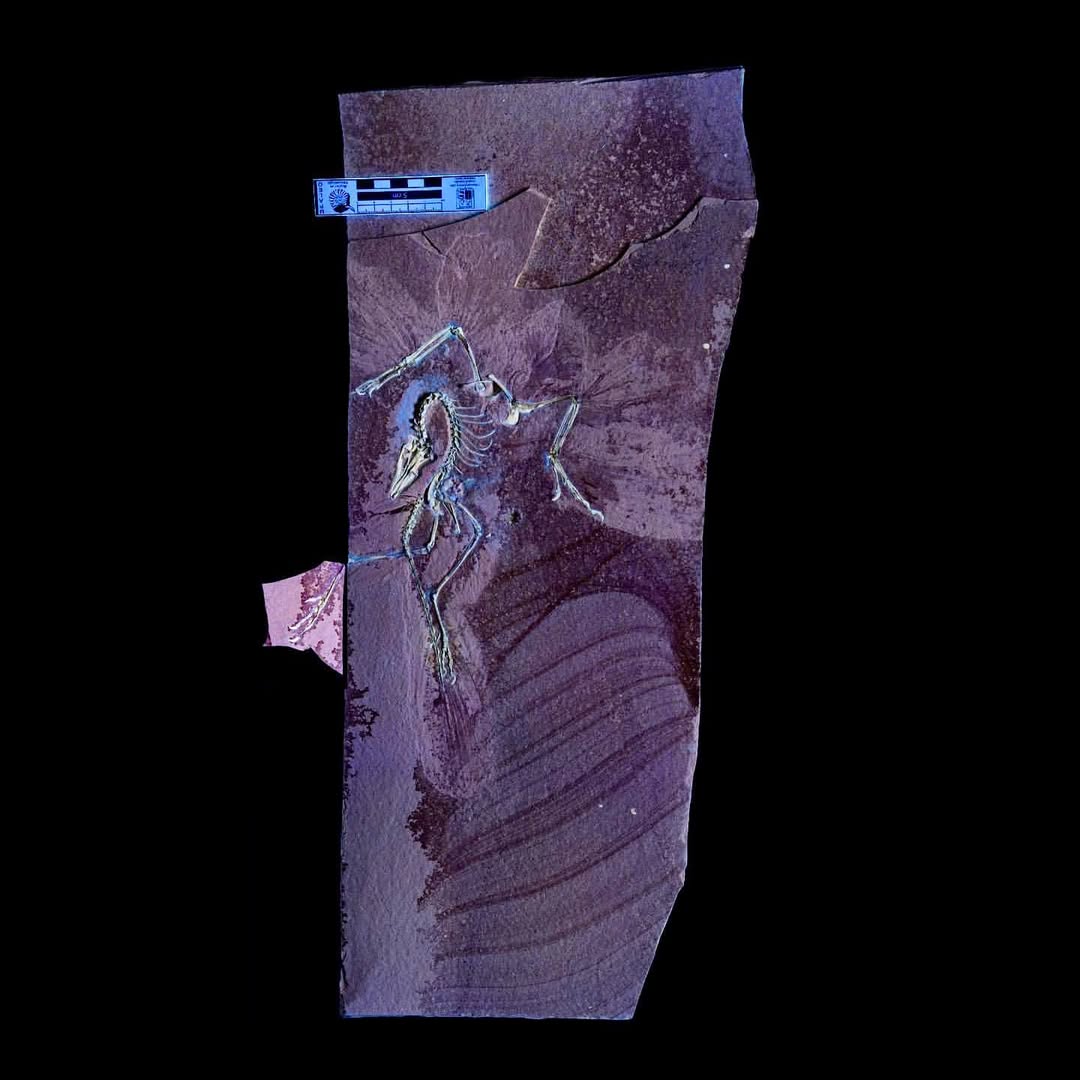

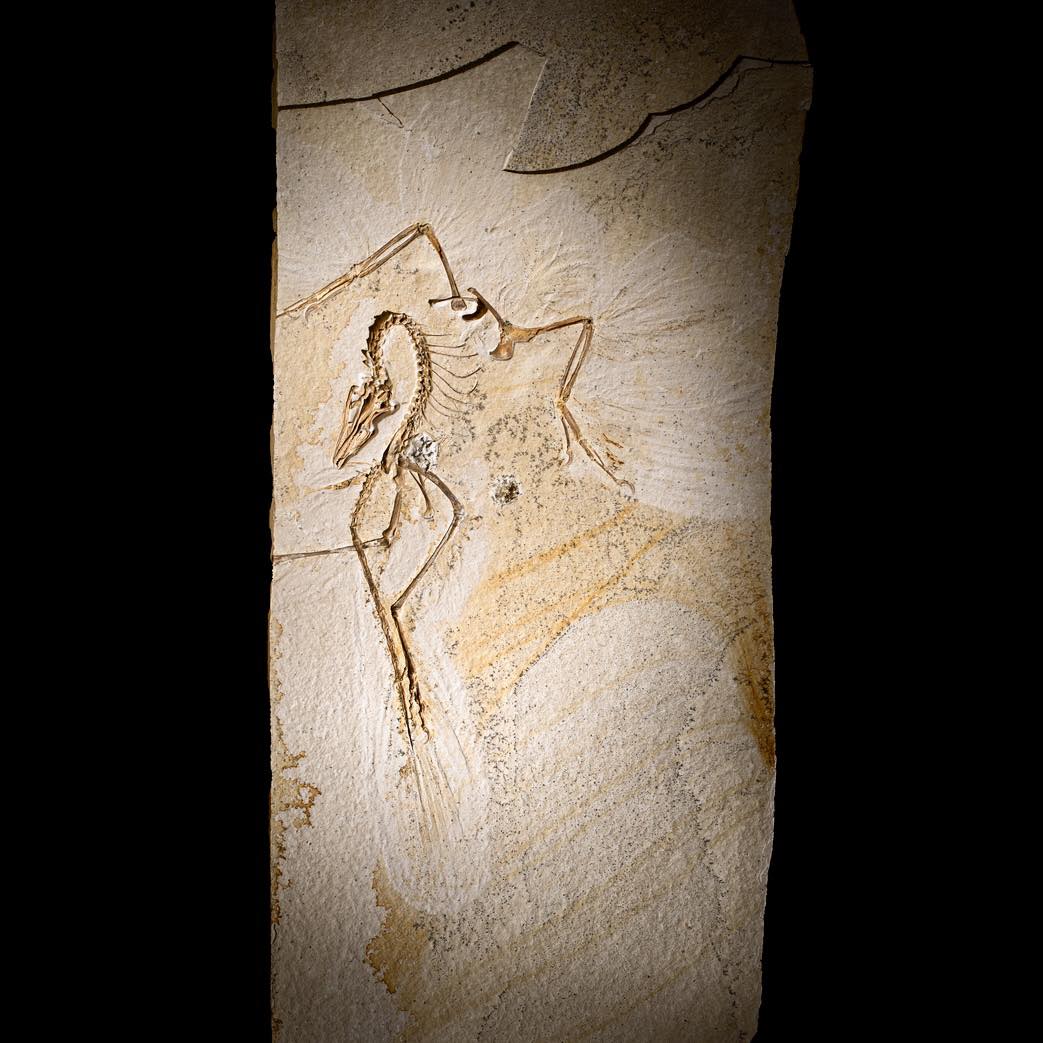

Archaeopteryx is perhaps the most widely known candidate for the “first bird,” although this title is hotly debated. While it bore many avian characteristics, such as feathers and a wishbone, it also retained several features not seen in modern birds – including sharp teeth, a long bony tail, and clawed hands. Scientists remain uncertain whether Archaeopteryx was capable of flight or merely glided between trees. Nonetheless, its discovery in 1861 remains a watershed moment in the study of evolution.

“Although you can’t unambiguously call Archaeopteryx a bird, it is unambiguously a dinosaur,” explains Professor Field. “It had some traits found in modern birds and others far more primitive, so calling it a bird doesn’t quite sit right – but it’s definitely close.”

Despite its age – roughly 150 million years – Archaeopteryx may continue to hold its iconic status more due to its early discovery than its actual position in the evolutionary timeline. Other contenders, such as Aurornis xii and Anchiornis huxleyi, date to approximately 160 million years ago and may represent even earlier stages in the bird lineage. These feathered species likely could not fly, instead using gliding as a means of locomotion. In the case of Anchiornis, preserved pigment structures have even revealed that its plumage was black and white, with a striking red crest.

++ Meta Taps AI Prodigy Alexandr Wang to Lead New ‘Super-Intelligence’ Drive

Bird-like species have existed since the Late Jurassic, but the earliest animal that is unquestionably a bird is the common ancestor of all living species. Scientists estimate that this ancestor lived between 100 and 85 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous, exhibiting defining avian features such as feathers, flight capability, hollow bones and a beak without teeth.

The earliest undisputed modern bird fossil is Asteriornis maastrichtensis, also known as the “wonderchicken”. Discovered in sediments dating to 66.7 million years ago – just 700,000 years before the mass extinction that ended the reign of the non-avian dinosaurs – the wonderchicken was a small, ground-dwelling species believed to reproduce quickly and fly with ease. These attributes may have given it an edge during a time of unprecedented ecological upheaval.

“The wonderchicken appears to be the most unambiguous early representative of Neornithes – the group that includes all modern birds – discovered to date,” says Professor Field. “It already had the full set of traits we associate with today’s birds, indicating that all those features had evolved before the end of the Cretaceous.”

Since those early beginnings, birds have undergone remarkable diversification. Today, more than 11,000 species fill nearly every ecological niche on the planet, from the flamboyant birds-of-paradise in tropical rainforests to the resilient emperor penguins of Antarctica.

But what enabled their survival when the asteroid impact 66 million years ago decimated the dinosaurs? Experts point to a combination of factors. The ability to fly gave birds mobility, allowing them to escape deteriorating habitats, seek out new ones, and eventually evolve into distinct species better suited to novel environments. Their beaks reflect this adaptability, having diversified to accommodate a wide variety of feeding strategies.

Crucially, survival may also have come down to something far less scientific – chance. “Birds came very close to extinction when the asteroid hit,” Professor Field notes. “Our evidence suggests that most bird-like species alive at the time perished. The odds were against them, much as they were for other dinosaurs.”

Ultimately, only a handful of bird lineages made it through the extinction event: the Galloanserae (ancestors of chickens, ducks and other fowl), the Palaeognathae (such as ostriches and emus), and the Neoaves, which make up 95% of today’s bird species. These survivors were mostly small, terrestrial birds capable of rapid reproduction and fast adaptation to the treeless post-impact world.

“I think luck played a big part,” Professor Field concludes. “It may sound unscientific, but we have to acknowledge it. The world came close to losing birds – and with them, the last living dinosaurs. I, for one, am grateful they’re still here.