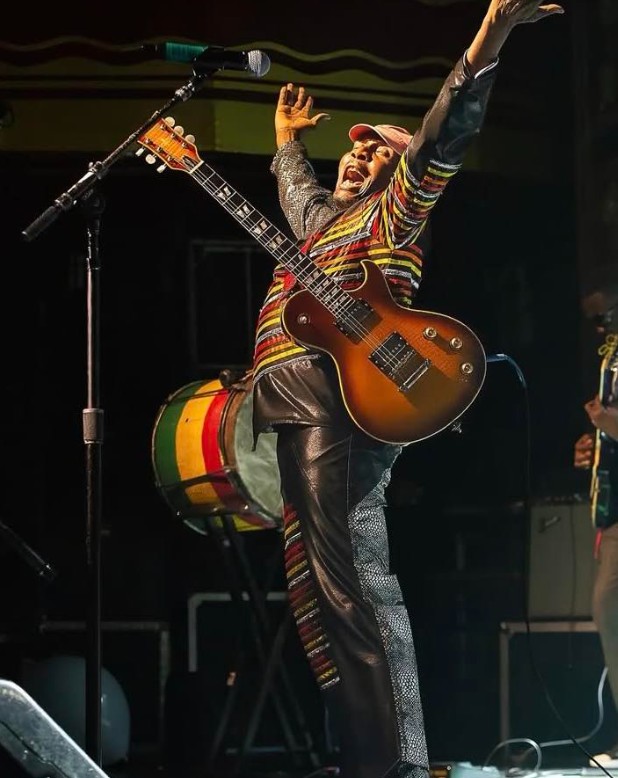

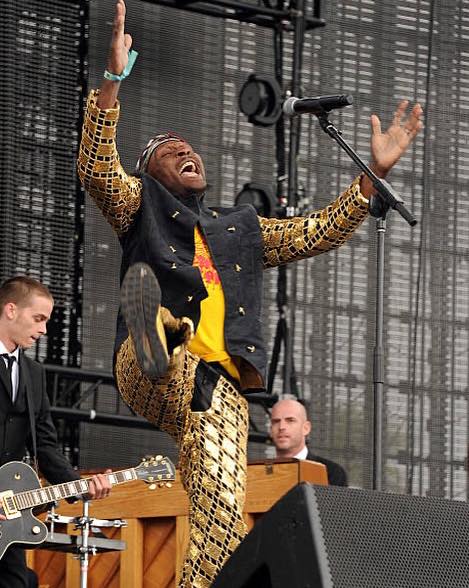

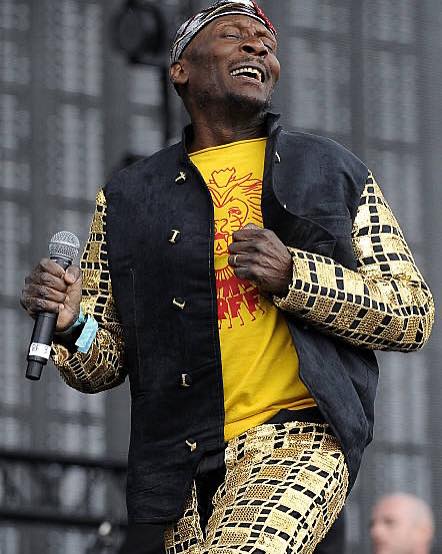

Jimmy Cliff, the celebrated Jamaican singer-songwriter and actor behind classics such as You Can Get It If You Really Want and Many Rivers to Cross, has died at the age of 81. The news was confirmed by his wife, Latifa, in a message shared on Cliff’s official Instagram page. “It is with profound sadness that I share that my husband, Jimmy Cliff, has crossed over due to a seizure followed by pneumonia,” she wrote. She expressed gratitude to family, friends, fellow artists and colleagues “who have shared his journey with him”, and thanked fans whose support “was his strength throughout his whole career”.

++ London aquarium faces renewed scrutiny over penguin welfare

Ms Chambers added that her husband deeply valued “each and every fan” for their affection and paid tribute to the medical team who were “extremely supportive and helpful during this difficult process”. Signing off with a personal farewell, she wrote: “Jimmy, my darling, may you rest in peace. I will follow your wishes. I hope you all can respect our privacy during these hard times.” The message was also signed by the couple’s children, Lilty and Aken.

Jamaica’s prime minister, Andrew Holness, led tributes, describing Cliff as “a true cultural giant whose music carried the heart of our nation to the world”. He added that Cliff’s songs “lifted people through hard times, inspired generations and helped shape the global respect that Jamaican culture enjoys today”.

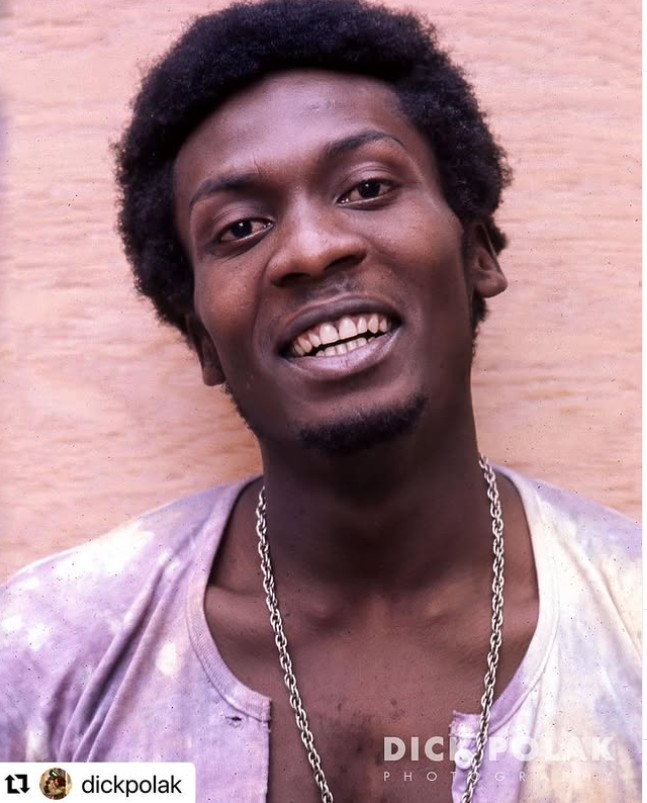

Born James Chambers in the village of Somerton, Jamaica, on 30 July 1944, Cliff was one of nine children raised by their father in a modest three-bedroom home. He became a local sensation at the age of six, performing in his church thanks to his striking voice. Radio broadcasts of Jamaican music later inspired him to pursue a professional career. At 14, he moved to Kingston and, five years later, achieved his first hit with Hurricane Hattie.

“Kingston was rough,” he recalled in a 2003 interview with The Independent. “In the city you know no one. You can’t go to your neighbour like in the country and say, ‘I’m hungry, give me something.’ But even then I knew what I wanted. I had songs I had written and wanted them recorded. It wasn’t about money – it was about getting my art exposed.”

By his mid-twenties, Cliff was an international success, propelled by singles such as Wonderful World, Beautiful People and Vietnam, the latter praised by Bob Dylan as “the best protest song”.

++ Fish facts that challenge what we know

His breakthrough into global cinema came with the 1972 film The Harder They Come, in which he starred and contributed to the soundtrack. The film, credited with bringing Jamaican music and culture to international audiences, almost didn’t feature Cliff. Writer-director Perry Henzell travelled to the UK, where Cliff was preparing for a major tour, to persuade him personally. “He said one sentence that stopped me in my tracks,” Cliff recalled in 2022. “‘I think you’re a better actor than a singer.’ I thought, ‘Wow! Somebody’s reading my mind.’ I cancelled the European tour and went to do the movie.”

The soundtrack, featuring Cliff alongside acts such as Toots and the Maytals and Desmond Dekker, became a landmark of Jamaican music. Despite the film’s acclaim, Cliff returned to music afterwards. “I went into it thinking I’d do this piece of work, and then I’d go back to touring,” he said.

In 1993, his version of Johnny Nash’s I Can See Clearly Now, recorded for the film Cool Runnings, reached No 18 on the US Billboard Hot 100. His celebrated rendition of Cat Stevens’ Wild World came after Cliff heard the demo at Island Records in 1970. When Stevens expressed uncertainty about releasing it, Cliff told him he would record it himself. The track became Cliff’s first UK Top 10 single – after which Stevens also released his own version.

Cliff was later awarded the Jamaican Order of Merit, joining a distinguished list that includes Bob Marley and Bunny Wailer. Although some fans believed he ceded global recognition to Marley, Cliff rejected the idea that he should have remained strictly within reggae. “If I put me in this one little bag, I’m going to be suffocated,” he said. “They say, ‘You’re a Jamaican, you’re known for reggae,’ but I won’t. I’ve done my part; now I’m on another path.” He maintained that creative exploration was central to his career. “Looking for the new – that’s fundamental to me.”